The One Earth Series

Alicia Bravo and Manuel Espinosa

Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas Margarita Salas, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). Ramiro de Maeztu, 9. 28040 Madrid, Spain

This series comprises four Chapters devoted to describing the One Earth concept. We shall discuss the relationships between two separate, albeit intimate, beings sharing the same niches in many cases: Humans and Bacteria. Why are we afraid of Bacteria? Will Bacteria kill us all? How can we defend ourselves from their deadly attacks? Must we share the same niches? These and many other questions will be raised and discussed here. But we can anticipate the answer: We must share, we must co-exist. Else, Humans will be doomed.

CHAPTER I. FINDING BALANCE: THE HARMONY BETWEEN HUMANS AND BACTERIA

Introduction

Two weeks ago three friends went on a 7-day vacation on the Mediterranean coast. When they got back, they told us about their little adventure. Everything was fine until the third night when one of them (let’s call him X) awoke with stomach pains and strong diarrhoea. He spent an awful night, you can imagine, but since there were no other symptoms (fever, nausea), X did not go to a pharmacy to get a prescription. The two other people did not suffer any problems. Analysing what could have caused his sickness, they discovered that the difference between them was that X had drunk a soda with ice on it while the other two had a coffee each. Soda had never caused a problem to X's bowels, so they concluded that the cause was the ice –the water in the ice! X asked a waiter, and he answered that they normally use tap water to prepare the ice cubes. Could it be that X had a weak intestinal infection? It was cured after a few days of eating yoghurt and a soft diet. Has this ever happened to you too? Well, then, let’s talk about our microbes within (and without).

The microbiomes

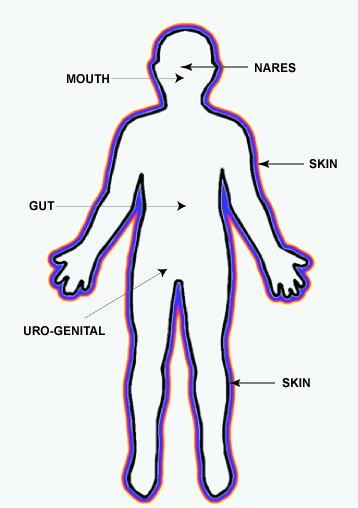

Imagine that inside (and outside) our body exists a vast world of tiny organisms, which we call microorganisms because they are only visible when observed under a microscope. They live inside (and outside) our body in different communities that are located in our skin, nares, mouth, nasopharynx, guts, and genitals (see Figure 1). They constitute microbial communities that we call microbiomes. Many of these microscopic beings are called bacteria (the singular is “bacterium”), although there are other microbiome members, such as viruses and fungi. These plethora of beings are not random invaders or parasites. We are born with a part of our, still immature, microbiome inherited by our mothers and some bacteria accompanying us while we pass the vaginal tract during birth. The components of our microbiome play a crucial role in our health and well-being. And, in turn, our feeding habits will determine which bacteria will be in our microbiomes (especially in the gut microbiome) and which bacteria contribute to our health and which do not. Our social life, age, dietary habits, and economic status define the composition of the gut microbiome and, as a result, have an impact on our general well-being. Further, these bacteria could influence some of our decisions because the microbiome may affect our production of neurotransmitters. This, in turn, will affect our mood and attitude when confronting our everyday problems and choices.

Curiously, many herbivorous baby animals (from cows to elephants) eat part of the faeces of their mothers as a way to adapt their gut microbiome from milk to grass (Figure 2). This is especially important to animals like panda bears, which are bamboo eaters, and koalas, which eat eucalyptus leaves that is a food extremely poisonous to many animals. Fortunately, we, Humans, do not share these habits. However, today’s exploration of the human gut microbiomes may recommend a faecal transplant as a treatment for some diseases, as we shall see in a later Chapter.

Our Bacterial Neighbours Within

Trillions of bacteria call your body home: we can estimate that in any healthy individual, there are around two bacterial cells per single human cell. The latest measurements have estimated a total of 30 trillion human cells per adult male and 28 trillion cells per adult female (that is, 30 and 28 followed by 12 zeros). This gives us an idea of the number of bacteria per healthy individual: we have learned to use huge numbers to count them! (https://www.livescience.com/new-metric-measurement-prefixes).

We should count our bacterial inhabitants as co-workers rather than enemies. It is important to stress that bacteria are not harmful parasites or intruders within us. On the contrary: they protect us against harmful environmental conditions, they help us to digest our food, and they provide us with essential nutrients like some vitamins that we cannot obtain from other sources. Of course, these benefits to us are not for free: bacteria also get, from us, a niche where to live and food for their growth. In many cases, our gut-associated bacteria will help us in case of acid indigestion and can even protect us from harmful pathogens.

But Bacteria not only colonise our bodies. They are also present in our homes, especially in the bathrooms and kitchens. Microorganisms are also present in our keyboards and screens of computers, in our clothes, and everywhere around us (see “Further Readings”, in Spanish, below). Even more, microbial communities have been found on the surface of plastic debris submerged in rivers (Medical News, October 31st, 2023; “Further Readings”, in English, below).

Must we become hysterical about these facts? Indeed, no. We have to face the truth of these facts and not to panic. Rather, we must learn how to cohabit with our microscopic neighbours. Further, we should be aware that we cannot eliminate all microorganisms around us and that maintenance of our well-being is achieved by cleaning routines without the overuse and misuse of antimicrobial cleaning products. Such misuse will contribute to the selection of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms, which may be a big problem, as we shall describe in Chapter II.

The Gut-Brain Axis

Our gut microbiome is often called our "second brain" because the products of bacterial digestion can pass the so-called “gastro-intestinal barrier” and communicate with our brain, influencing our emotions, proper rest and well-being. In other words, when our gut bacteria are happy and healthy, we tend to feel better too. Thus, a complex bidirectional interaction exists between the gut and the brain, which is mediated by the microbiome, the endocrine and immune systems, and other pathways. It is admitted today that there are bidirectional communications between the central and the enteric (gut) nervous system. That is, between our intestinal microbiome and our brain and vice versa. These communications result in a linkage between the emotional and cognitive centres of the brain with intestinal functions (digestion and well-being). Thus, interactions between gut-microbiome and brain appear to be achieved by signalling from gut-microbiome to brain and from brain to gut-microbiome through neural, endocrine, and immune links. (Carabotti et al., 2015). To make things a bit more complicated, we now know that sex differences (hormones, for instance) influence the bacterial composition of the human gut microbiome, and it is now admitted that there is a greater diversity of species in females.

The gut-brain axis has been implicated in many disorders from anxiety and depression to Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Although no direct proof has been yet achieved in the latter two diseases, it has recently shown a direct relationship between mental stress and irritable bowel syndrome (Shobeiri et al., 2022).

The Bacterial World

The best-understood players in the interactions between humans and microorganisms are bacteria. We are going to initiate an exploration of the delicate balance between Humans and these tiny but powerful residents of our bodies in the following Chapters. We shall be going through different stages to learn how to reach an understanding between Bacteria and us. The underlying message is going to be the urgent need for an understanding between Humans and Bacteria worlds, within a concept that we have termed One Earth. This concept considers the bacterial world as an essential component of our health, the biodiversity of our planet, and in the long run, an essential participant in the solution of climate change crisis. We shall try to convey the message of the need to understand the benefits of bacteria in our everyday lives and reach an entente cordiale between Humans and Bacteria. This is our only alternative left.

Further Readings:

In Spanish:

https://www.eldiario.es/consumoclaro/lugares-con-mas-germenes-casa_1_10627535.html.

In English:

Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M.A. and Severi, C. (2015) The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol., 28, 203-209.

Shobeiri, P., Kalantari, A., Teixeira, A.L. and Rezaei, N. (2022) Shedding light on biological sex differences and microbiota–gut-brain axis: a comprehensive review of its roles in neuropsychiatric disorders. Biol. Sex Differ., 13, 12.

Acknowledgements

This series attempts to communicate our research at the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas Margarita Salas, CSIC and is part of the Grant I+D+i PID2019-104553RB-C21, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. Thanks to María del Carmen Fernández and Mónica Fontenla for their help during the elaboration of this series.

Other chapters

Chapter II: link.

Chapter III: link.

Chapter IV: link.